Death Row Savior

The Baymont Inn stands on the western edge of Nashville, just off interstate 40, a cheap, anonymous motel with little to differentiate it from the other neon-lit road houses all vying for transient trade nearby. As the rush hour traffic swarms out of the city at around 6pm on a grey Thursday evening, a beige Geemarc phone chirrups with bland urgency in room 106.

The receiver is snatched out of its cradle and after a few mumbled words - replaced. “We’ve been denied: the US supreme court has ruled against us,” says Joe, a towering man with a gold crucifix slung around his neck, stoop shouldered, his face now unable to disguise despair. A few days earlier he had said tonelessly: “Welcome to the machinery of death – up close and personal - it just keeps on running.” The red LCD digits of a cheap bedside clock change with the minute and now Joe’s words are proving increasingly prophetic.

In around seven hours time, Philip Workman, 43, father of two and grandfather of three will be led out of the sterile confines of the Death Watch area of Riverbend Maximum Security prison about five short miles away. Shackled and dressed in a clinical white paper jump suit, he will be strapped to a gurney, restrained with leather straps and wheeled into the grey-green death chamber by an execution team.

On the gurney two intravenous drips with three inch stainless steel needles will be forced into either arm. If the executioner can’t find a vein they will perform a “cut down,” and his arms will be scalpelled open and the catheters inserted into his bleeding forearms. A saline solution will then be pumped through transparent plastic tubes, closely followed by a deadly cocktail of drugs. First sodium thiopental will be administered which, it is hoped, will send him to sleep. Then pancuronium bromide, a muscle relaxant, will be injected which will paralyse his diaphragm and lungs. If that fails to kill him a further ingredient of potassium chloride will cause a heart attack. No-one really knows how it feels - apart from killing you - just that a prisoner in another state had such a violent reaction to the injection before issuing a death rattle that a witness fainted.

Terry, his brother, a laconic, bow legged Kentuckian and former truck driver sucks on a Kool menthol after hearing the news. He will be there to witness his brother’s killing: the end of his life and the wheeling out of his ashen corpse. “If they kill my brother I don’t know how I’ll hold up,” he had confided a few days before. In the motel room too is Lori, Philip’s girlfriend, a diaphanous blonde country singer who came to Nashville to find music and inspiration, but found love with a convicted prisoner who has been on death row for twenty years. She breaks down uncontrollably in deep, reverberating sobs. She runs to the bathroom closely followed by Joe, the family’s lynchpin, who has held the family and Philip together through the years. He comforts her as she buries her head in his shoulder. The atmosphere is so leaden you can barely move your hand through the air.

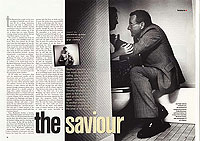

Half an hour later, Lori calmed, Joe comes back into the room and his eyes fill up with tears. He fights to hold them back. Then he picks his inky black cowboy hat from the bed and dumps it on his head, smoothing the brim with thumb and forefinger and pulling it low over his eyes. From here he will take the short drive to the prison where he will minister to Philip on death watch for his final hours up to the execution. Joe is a United Church of Christ minister, a southern preacher who has made death row his calling.

He instigates us all to form a circle of prayer, holding hands and once the benediction is over he exhales deeply. He hugs everyone. “We are dealing with the cosmic forces of evil here,” he says earnestly. “It has a corrosive effect on everyone it comes into contact with: the lawyers, everyone. It is the power of evil. It will suck you in. But we’ll get through this and when I come back we will all collapse together. ” He turns on his heel and leaves the room in edgy silence.

This is the third time in a year Philip has been moved to death watch, the last two executions were thwarted by last minute appeals but this time the prognosis looks bleak. The appeals process is almost exhausted. Over the next few hours what happens between the four walls of room 106 will run the whole vivid kaleidoscope of human emotion as time circles - seemingly to the inevitable.

These days the southern Bible belt has also earned another sobriquet: the “death belt.” Here in the heart of the south the Reverend Joe Ingle has “lost twenty one friends to the executioner.” For a quarter of a century he has been answering ‘God’s call’ to defend those condemned to death in the deep south of the United States by comforting families in their hour of need, supporting the condemned in any way he can and fighting to abolish capital punishment.

It has been costly. While he has twice been nominated for the nobel peace prize in 1988 and 1989, his campaigning has led him to being arrested (once on the steps of the supreme court), he and his family have received death threats and he’s even been charged with murder for helping, it was claimed, foment a prison riot where prisoners were killed. The charges were later dropped. “Yup,” he says, with a mischievous grin. “Ah made a lot of powerful enemies.”

His passion for civil rights and social justice was annealed in the claustrophobic heat and humidity of north Carolina. He speaks in the slow, deliberate vowel flattened drawl of the south. Born into a white, middle class and god-fearing southern Presbyterian family in the cataclysmic era of segregation and rampaging Klu Klux Klan claverns, “Racism,” he says, “was a way of life.”

“My aunts and uncles would say nigger this and nigger that all the time,” he says. “And I remember once in the car with my aunt remarking on the pretty dress a black lady was wearing. My aunt walloped me saying, “Don’t ever let me hear you call a nigger a lady again.”

His mother, however, was a liberal voice of dissent and it was her who first implanted the seed of justice and equality. In his teens, he was caught at a Black Panthers meeting. Shortly afterward, at St Andrews Presbyterian college, Laurinburg, North Carolina the “white boy who had never cussed or drank a beer” became a rampant political force. Heavily involved in civil rights he organised a march when Martin Luther King was assassinated and campaigned against the Vietnam war in between studying western philosophy and religion.

But the conservative values of the south began to take their toll on a highly sensitive and politicised young “apostle of Christ.” Following college he went to seminary in Richmond, Virginia. There too his ideas met with resistance. “I mean we just put out an alternative Christian newspaper about what it meant to be a Christian and a lot of people started to act as if we where going to burn the place down or something.”

Once ordained, with little direction and depressed with the conservative attitudes of his professors at the seminary he moved to New York, where the liberalism of the north was a tonic to his tortured spirit. It wasn’t the first time either he would run to the north to escape the killing and bigotry of the south. “But I just knew that I didn’t want to have a church and a congregation – it just wasn’t my fit.” It was while at seminary in east Harlem in 1971 that flickering images on his fuzzy black and white TV of a prison riot at Attica, upstate New York brought him to an epiphany.

“I was a white boy up from the south in a major urban ghetto and I had no experience of jail. It made me wonder who is locked up, executed and why? You’re not taught that in Sunday school or in theology college either.” He began to visit the prison and made close friendships with 44 inmates and found his calling. “This is what God wanted me to do.” His motivation is clear. “Jesus Christ was the first victim of the death penalty.”

Joe returned to the south in 1974, married and started visiting prisoners at the start of the year. It was a crucial time. In 1972 the US supreme court had struck down a motion to reinstate the death penalty saying it was unconstitutional but when Ingle returned that year death row cells started to fill up again when various southern states passed new laws reinstating executions. Ingle with the Committee of Southern Churchmen began work with a new organisation called the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons.

Over the years he would work all over the south from Louisiana to north Carolina and Florida, working with lawyers protecting the family and providing help, support and spiritual existence to men and women condemned to die. Nothing got in his way. In 1984 he staged a protest at a meeting chaired by the Governor of Florida in his cabinet office with other protestors who wore black hoods while staging a mock execution. Using the same tactic outside the US supreme court with a fake electric chair he was arrested in Washington DC. And in a bid to drum up support from celebrities to raise the profile of the abolitionist campaign he crashed the set of MASH and got Mike Farrell who played B.J. Hunnicutt to campaign against the death penalty. No stone was left unturned and once he drove the family of a condemned man out to the state governor’s mansion to plead with him to spare his life (the state governor can rule clemency and the execution process is stopped).

And his first execution he remembers with a faraway, darkening of his features. John Spenkelink was executed by electric chair in Florida for the murder of a man who had brutally abused him in May 1979. “When they killed him I was in a hotel room with his mother and had to escape,” he says. “I went into the bathroom turned all the taps on so she wouldn’t hear me and with tears running down my eyes screamed ‘God why is there no justice?’ I’ve lost faith in God a few times in this work but I think everybody has at some point. After John Spenkelink was executed I vowed I would never get this close to anyone again. But you can’t help it. You can’t work with folks like this and not get close to them.”

Yet over the years the work has taken its toll often leaving him severely depressed. In 1991 he took a sabbatical and went north a second time to study at Harvard. “I was wiped out emotionally seeing so many people killed,” he says. “When I got there two things were possible: Either I was insane for what I was doing or society was out of step. Everything I had believed in like the Judaeo Christian tradition and democracy had been smashed to smithereens in front of my face. I had done everything to stop these executions.” Yet after a while he returned to the south to carry on his work. John Spenkelink was the last time I screamed at God and often it does seem as though he is absent. Last week I screamed again though about Philip Workman. If he is executed I will go north again.”

Philip Workman’s case has been remarkable in that it has transformed some attitudes in a staunchly pro-capital punishment state. Workman, a cocaine addict at the time, made a clumsy attempt to rob a Wendy’s restaurant in Memphis in 1981 at gunpoint. He was caught, a firefight ensued and police officer Ronald Oliver was shot dead. Workman got the death penalty.

Over the ensuing years on death row discrepancies in the case and new evidence have thrown his murder conviction into real doubt. A medical examiner from Georgia signed an affidavit saying Workman’s bullet could not have killed the police officer. More than likely, argued lawyers, he was killed accidentally by his own colleagues. And the state’s chief witness, a drug addict, later admitted he perjured himself in court afraid of what the police would do to him and his family if he didn’t. Many Tennesseans believe the state is executing an innocent man.

“It’s very clinical and methodical here - quiet,” says Philip from his cell on deathwatch, two days before the execution. He is only allowed to call ten numbers and media interviews have been prohibited. However, I get access and as we talk the whirr of a prison tape recorder in the background causes static on the line. “I wouldn’t wish this on anybody. The not knowing is the worst, the realisation that if the courts don’t do the right thing then these men will come in and do their job and kill you. The absurdness of it all. I get lethal injection because it’s a more acceptable way to kill, its more humane.” He laughs, darkly. “Its like killing a dog – immunisation. More acceptable see.”

Yet he attests to the help Joe has given him. “Joe is like a rock. I feel privileged to know him and he is dedicated to helping people like me in this situation.”

Its Tuesday, two days before the execution. The call over, Joe disappears outside on his porch leaving me in the room with his wife Becca. She bears the brunt of Joe’s tortuous work. “Oh God I don’t know how we’re going to cope,” she says, forlornly. A nurse on a cancer ward she has a steely but kind and stoic resolve. She puts one in mind of the southern actress Andy Macdowell, having the same way of creasing her eyes when she laughs gently with patience and kindness. “Before he would go away and when he came back we had to cope with the depression and grief but this time it involves the whole family.” Joe’s adopted daughter Amelia, writes and speaks to Philip on a regular basis and Becca too has become close to him.

“This is the first time he has witnessed this close and I don’t know what its going to do to him,” she continues. “He’s often said if he looked at what they did he might not be able to carry on anymore.” Joe’s resilient passion has cost the family a lot and for five years Becca had to support them.

Joe outside is downcast and bitter. A further appeal has been turned down. His phone rings constantly, if not distraught family members, lawyers or Philip. “You have just spoken to a man who has come into his own on death row, become a leader and completely reformed. Now they wanna kill him. We’re right up against the wire with this. Basically we’re in a world of trouble,” he says, looking out into the cold Tennessee night, hopelessly. “They’re killing a man for political gain – its about money and power,” he says, after the Governor turned down an appeal for clemency. Does he see any conflict of interest working so closely with politics and being an ordained minister? “No,” he says, blankly. “It’s the same.”

Over the next two days we trail him around Nashville in his battered Buick Le Sabre – his mother’s old car. He takes care of the family as well as Philip in a dizzyingly complicated schedule. Joe hired an investigator to find Philip’s estranged wife and son, Domi a ten year old with an electric shock of blonde hair and liquid blue eyes. The spitting image of his father. They are subpoenaed to appear at the prison for a last visit. Joe goes to pick them up at the airport and finds someone has tipped off the press. Hungry film crews catch them coming off the plane to Joe’s dismay. “Vultures,” he spits. After the visit, Joe is waiting outside with the car and Domi climbs in the back seat. He clutches a plastic prison visiting room drinks voucher tightly. When asked what it is he says. “It’s a souvenir, my dad says I won’t be coming to visit him anymore.” The mood in the car reverts to pregnant silence.

Joe organises all visits for the family, cutting deals with the warden for contact visits which are increasingly restricted as the execution date draws nearer. Again and again Joe is on the verge of emotional meltdown. The warden denies the family a contact visit to Joe’s exasperation. “What am I meant to do,” he says irascibly. “You have to take it from the warden and can’t get angry otherwise he won’t let you back in and you can’t go the other way and crumble because I have to be strong for these people [Philip and the family].” The last few day before the execution is spent visiting funeral homes, buying a coffin and organising a suit for Philip to be buried in. Plans are also afoot to organise a procession in downtown Nashville headed by Philip in the coffin.

In amongst all this the state has declared Joe cannot minister to Philip in his final hours and he is forbidden from entering the prison in the run up to the execution. Joe has to take out a writ against the state and the governor ruling it unlawful. “If I have to fight the state of Tennessee to give this man his last rights I will – tooth and nail. But if there was one writ I didn’t want to take out this would be it,” he says. On the day of the execution appears in court. Chancellor Ellen Lyle rules in his favour. “You have to fight these people every step of the way,” he says breathlessly, tearing out of court for a meeting at a funeral home.

The night of the execution at 6pm he takes a trusted TV reporter from Channel Two to Terry’s motel room. Nashville is ablaze with the impending execution, the media ransacking the town to find Terry.

The interview over we are all left silently in the chintzy motel room with its pastel green carpets, cheap prints of Spanish villas on the walls and tacky chipboard furniture. Joe urges everyone to read Romans 10 at 12.55am when Philip will be wheeled into the execution chamber. He says he will be reading it to Philip in his last minutes, his hand on his leg on the gurney before he leaves. The peculiar ordinariness of the room over the next few hours and outbreaks of silence are punctuated by the phone occasionally. Philip calls and Lori and Terry take turns speaking with him, hand cupped over the receiver, as the execution draws nearer. The TV is turned on briefly for an update and a TV reporter, with news of another failed appeal at 8pm says in grave tones, “Philip Workman will be facing the executioner tonight.” Hastily the TV is switched off, but not before Lori watching the screen intently, breaks down again. As the cathode light on the screen shrinks to a thin, white line and fades to darkness there is a crushing realisation that there seems to be nothing left.

Over the last few hours the mood vaults between forced joviality which everyone jumps on with eagerness and then slowly we crash down to earth again with a savage dose of reality realising what lies ahead. At 11.30 Terry sits down on the bed and without preamble reminisces in a kind of summing up of Philip’s life from birth to now – a stream of consciousness but obviously cathartic. At midnight he leaves the room to make the drive to the prison to see his brother killed. “If he doesn’t want me there but I am going to be there so he sees me among all the people witnessing who want him killed.”

We too make the drive to the prison along a dark road, only lit by intermittent street lamps casting eerie pools of light. State troopers are parked everywhere shepherding protestors to a field outside. Chain link fencing separates those for and against the execution. There are only four protestors for the killing, one wordlessly holds up a sign saying, “I Hope He Screams” an anorak hood and baseball cap obscuring his face.

The minutes close and then the unthinkable happens. A cheer goes up from the protestors. Amid the chatter and excitement someone says the Tennessee supreme court has come back with a stay of execution with a new court date to hear all the new evidence – exactly what everybody had hoped for. The mood is charged, people grinning wildly, hugging each other with abandon. Philip Workman has cheated death by forty minutes.

Inside the prison Joe had been praying and reading the bible with Philip. Out of the corner of his eye a news flash had run along the bottom of a TV screen proclaiming the news. Philip was told and according to witnesses reacted as if he had been punched in the chest, taking a step back. His mood turned again when the TV news reporter said the hearing would be held the next day. “I can’t wait anymore they’ve got to kill me now – tell them to go ahead,” is how one witness describes the condemned man’s reaction. The news came back that the hearing, was for a few weeks time. Celebration once again.

Back at the motel room the mood is jubilant. Terry returns first, grinning so hard you fear his face will split. The terse cowboy-type demeanour disappears and he hugs everyone in a hitherto unseen display of affection. Joe returns minutes later, ecstatic, charged. “Jesus kicked butt tonight!” he shouts beaming. “The Lord was with us.”

Incredulous, he slumps on the bed after a week of the most intense emotional turmoil and does something he never does. He swears. “The third fucking time we face the executioner and they’ve granted a full evidentiary hearing. We may yet see the day when Philip walks out of that prison a free man.”

The entire city comes alight. Phone lines are jammed. At home Becca and Amelia get the first of the death threats by phone as well as well wishers calling at 3am to say thank you for Joe and their work in helping save an innocent man.

In the ensuing days Joe seems in a befuddled daze. The quick temper and irascibility have receded. He was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis in 1986 and stress aggravates the symptoms. In a quiet moment as he relaxes in the garden in a hammock. I ask if he can ever see a time when he will stop doing this work. He looks at me incredulously. “What when the death penalty has been abolished you mean?”